Today is Tweed Day, but it doesn’t celebrate the woolen fabric favored by the British upper class for sporting outfits and by college professors for suede-elbowed lecture hall jackets.

Instead, Tweed Day is named for one of the most corrupt politicians in New York history. William Magear “Boss” Tweed was born on April 3, 1823. He began his political life in 1851 as a city alderman. Five years later, he was elected to a newly-established city board of supervisors and began to consolidate his power in Tammany Hall, the seat of the Democratic political machine in New York City.

Tweed once said, “I don’t care who does the electing so long as I get to do the nominating.” Candidates he backed were elected governor of New York, mayor of New York City and speaker of the state assembly. He installed allies in city and county positions as well; the network became known as the “Tweed Ring.”

He opened a law office in 1860 to extort money from corporations under the guise of high fees for his “legal services,” despite the fact that he was not a lawyer. He began purchasing acres of Manhattan real estate, then promoting the expansion of the city into those areas.

Eight years later, Tweed was elected to the New York State Senate and also became the official leader of Tammany Hall. In 1870, he and his ring passed a new charter that placed them in charge of the city treasury. They began to systematically drain the city’s coffers using fake vouchers and leases, padded invoices and other means.

Business leaders like John Jacob Astor turned a blind eye to Tammany Hall, as long as it continued to line their pockets and keep immigrants in line. But by 1871, it became apparent that graft had brought the city to the brink of financial collapse. In July of that year, 60 died in a riot between Irish Protestants and Roman Catholics at a parade. The city’s well-to-do began to feel threatened and blamed Tweed for failing to control the rabble and keep them safe.

Tweed was arrested and, while out on bail, campaigned for and won re-election to the state senate. He was rearrested and forced to surrender his city posts and resign as Tammany leader. In January 1873, his first trial ended in a hung jury. His second trial that November resulted in a fine of $12,750 and twelve years in prison. A higher court later reduced the sentence to one year.

Soon after his release in 1875, New York State filed a civil suit against Tweed in an attempt to recover $6 million in embezzled funds; he was arrested yet again and held in Ludlow Street Jail. He couldn’t post bail but was allowed home visits and took the opportunity to escape to Spain, where he worked as a seaman.

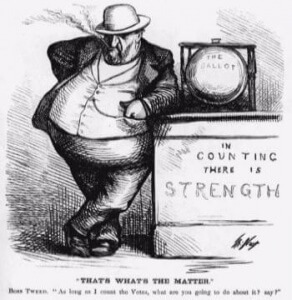

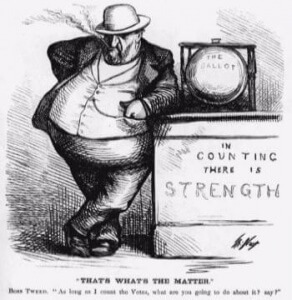

Tweed had long despised political cartoonist Thomas Nast, saying, “I don’t care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures!” His hatred deepened after someone recognized him from Nast’s drawings and turned him in. He was detained at the Spanish border and returned to the U.S. on an American warship.

After his return to Ludlow Street Jail in November 1876, Tweed agreed to testify against his former ring in exchange for his release. But after he had done so, the governor of New York reneged on the deal. He remained in the jail, where he died of pneumonia on April 12, 1878. His body was buried in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. In a final insult to the man who had ruled and robbed the city, mayor Smith Ely refused to fly City Hall’s flag at half-mast, traditionally done as a sign of mourning for respected public figures.

We’re not sure who chose this man’s birthday as a holiday, or why. While it’s easy to view Boss Tweed as an outlandish character governed by insatiable appetites, it’s important to remember that his exploits did not occur in a vacuum. They succeeded because of the implicit or explicit approval of all those who profited.

Of course, greed and corruption didn’t die with him. Perhaps the best way to learn from his life is to value compassion over avarice, to guard against the loss of concern for our fellow man, and to keep an eye out for the Boss Tweeds of today—so we don’t get fooled again.

National Beer Day commemorates a step in that direction. Under the Volstead Act, so-called “near beer” was allowed to have up to .5% alcohol because it couldn’t cause intoxication. Any higher percentage was considered liquor and forbidden.

National Beer Day commemorates a step in that direction. Under the Volstead Act, so-called “near beer” was allowed to have up to .5% alcohol because it couldn’t cause intoxication. Any higher percentage was considered liquor and forbidden.![]()