September 8 is Pardon Day

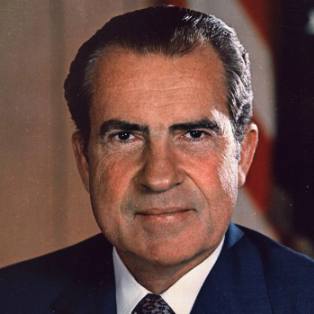

Today is Pardon Day. On September 8, 1974, President Gerald Ford issued a controversial pardon to Richard Nixon, who had resigned on August 9, 1974 (a.k.a. National Veep Day.) What follows is an excerpt. Read the full proclamation here.

As a result of certain acts or omissions occurring before his resignation from the Office of President, Richard Nixon has become liable to possible indictment and trial for offenses against the United States. Whether or not he shall be so prosecuted depends on findings of the appropriate grand jury and on the discretion of the authorized prosecutor. Should an indictment ensue, the accused shall then be entitled to a fair trial by an impartial jury, as guaranteed to every individual by the Constitution.

It is believed that a trial of Richard Nixon, if it became necessary, could not fairly begin until a year or more has elapsed. In the meantime, the tranquility to which this nation has been restored by the events of recent weeks could be irreparably lost by the prospects of bringing to trial a former President of the United States. The prospects of such trial will cause prolonged and divisive debate over the propriety of exposing to further punishment and degradation a man who has already paid the unprecedented penalty of relinquishing the highest elective office of the United States.

Now, THEREFORE, I, GERALD R. FORD, President of the United States, pursuant to the pardon power conferred upon me by Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution, have granted and by these presents do grant a full, free, and absolute pardon unto Richard Nixon for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 20, 1969 through August 9, 1974.

Gerald R. Ford

The scandal leading up to Nixon’s resignation came to be known as “Watergate” because of the first crime officially attributed to Nixon’s “dirty tricks” campaign. On June 17, 1972, five men were arrested for breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate building in Washington DC, placing wiretaps and stealing records. (An earlier break-in, in May 1972, had been successful but the audio quality of the bugs was considered unacceptable, necessitating another trip.) The burglars were carrying cash from the campaign fund. Two more men were later indicted in the case.

On July 16, 1973, White House aide Alexander Butterfield revealed in a televised hearing that the Secret Service had, at Nixon’s behest, installed a recording system in the White House in February 1971. According to information on file at the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, seven microphones were placed in the Oval Office: five in his desk and one on each side of the fireplace. Two more microphones were installed on the underside of the table in the Cabinet Room.

In April 1971, Secret Service technicians installed four microphones in the desk of the president’s private office in the Old Executive Office Building. They also tapped the telephone lines there, in the Oval Office and in the Lincoln Sitting Room, which was Nixon’s favorite room in the White House. In May 1972, they placed a microphone in Nixon’s study at Camp David and tapped the phones on his desk and on a nearby table.

He was not the first president to record meetings; the practice dates back to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s time in office. But Nixon’s system was voice-activated so he wouldn’t have to press a button to capture conversations. His convenient disregard for the need to judge which conversations merited violation of privacy meant that everything he’d said, including self-incriminating statements, had been preserved.

Chief Judge John Sirica of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, presiding over the trial of the Watergate burglars, saw an opportunity to confirm his suspicions that they hadn’t acted alone. He ordered President Nixon to turn over nine tapes of 64 White House conversations to Archibald Cox, the special prosecutor in charge of investigating the allegations of Nixon’s misconduct.

Richard M. Nixon

Nixon refused, citing Constitutional separation of powers, executive privilege and national security concerns. On October 19, 1973, Nixon proposed that U.S. Senator John Stennis, a Mississippi Democrat, review the tapes and report his findings to Cox as a compromise. When Cox rejected the offer, Nixon ordered Attorney General Elliot Richardson to dismiss him; he refused and resigned.

Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus was approached and also refused to follow the president’s directive, generating such ill will that his firing was announced by the White House while he was in the midst of writing his letter of resignation. Solicitor General Robert Bork became acting Attorney General and immediately fired Cox per Nixon’s instructions.

Bork’s dismissal of Cox was challenged in a lawsuit filed by consumer advocate Ralph Nader and others. Per the New York Times:

On Nov. 14, 1973, Federal District Judge Gerhard A. Gesell ruled that the dismissal of Mr. Cox, in the absence of a finding of extraordinary impropriety as specified in the regulation establishing the special prosecutor’s office, was illegal.

The Justice Department did not appeal the ruling, and because Mr. Cox indicated that he did not want his job back, the issue was considered moot.

In a memoir published a few months after his death in 2012, Bork claimed that Nixon promised him the next available Supreme Court seat in exchange for doing his bidding. This would seem to contradict his repeated assertions that he had acted purely in the interest of the law, believing that Cox did not have the authority to prosecute the president.

Bork was finally nominated to the Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1987. His actions of fourteen years earlier were savaged by press and politicians, contributing to his defeat and the addition of his name to the lexicon of English slang.

bork

transitive verb \ˈbȯrk\

:to attack or defeat (a nominee or candidate for public office) unfairly through an organized campaign of harsh public criticism or vilification

Even with Bork’s willing participation, Nixon’s efforts were in vain. After he appointed Leon Jaworski to replace Cox, the new special prosecutor issued a new subpoena for the same tapes, chosen to confirm or refute the damning testimony of former White House Counsel John Dean.

Hoping to mollify the judge and the public, Nixon turned over edited transcripts of 43 conversations, including portions of 20 of the conversations cited in the subpoena. Nixon’s attorney, James St. Clair, moved to quash the subpoena, stating:

The president wants me to argue that he is as powerful a monarch as Louis XIV, only four years at a time, and is not subject to the processes of any court in the land except the court of impeachment.

Sirica denied the motion and ordered the president to turn the tapes over by May 31, 1974. Both Nixon and Jaworski appealed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court to intercede. It began hearing arguments in the case, United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, on July 8, 1974.

The court wished to reach a unanimous decision on an issue of such gravity so Judge William Rehnquist, appointed by Nixon, recused himself from the proceedings. On July 24, 1974, it upheld Judge Sirica’s ruling 8-0. Nixon was forced to hand over the requested recordings, but there was an 181⁄2 minute gap in a June 20, 1972, audio tape.

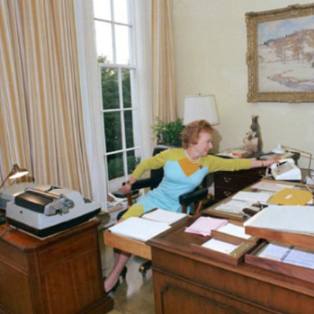

Secretary Rose Mary Woods claimed responsibility for up to five minutes of the erasure, although her demonstration of how it could occur, requiring the simultaneous and continuous pressing of controls several feet apart, strained credulity. The press dubbed the maneuver the “Rose Mary Stretch.” The contents of the gap remain a mystery.

Wood demonstrates how she could have erased tape.

Nixon had good reason to fear the release of the tapes. In one conversation on June 23, 1972, six days after the arrests, he told Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman to strong-arm Richard Helms and Vernon Walters, director and deputy director of the CIA, and convince them to advance a bogus national security reason for the break-in and advise the FBI to cease its investigation.

The president expected compliance because his administration had, as he put it, “protected Helms from one hell of a lot of things.” He instructed Haldeman:

When you get in these people when you…get these people in, say: “Look, the problem is that this will open the whole, the whole Bay of Pigs thing, and the President just feels that” ah, without going into the details… don’t, don’t lie to them to the extent to say there is no involvement, but just say this is sort of a comedy of errors, bizarre, without getting into it, “the President believes that it is going to open the whole Bay of Pigs thing up again. And, ah because these people are plugging for, for keeps and that they should call the FBI in and say that we wish for the country, don’t go any further into this case,” period!

The Bay of Pigs Invasion was a failed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro in Cuba. The paramilitary group that carried out the attack on April 17, 1961, had been trained and funded by the CIA. When the operation was exposed, it caused embarrassment to the agency and to President John F. Kennedy, who had approved the action.

Nixon’s reference to the “Bay of Pigs fiasco” was meant to raise the specter of a shameful episode in the CIA’s past while implying that another could be engineered if Helms didn’t cooperate. He refused. On November 20, 1972, the president summoned Helms to Camp David and informed him that his services were no longer required. He appointed him Ambassador to Iran to keep him in the fold.

******

Three days after the Supreme Court’s ruling, the House Judiciary Committee issued the Articles of Impeachment, which concluded that Nixon maintained a “secret investigative unit,” funded in part by the Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP). He used the resources of the FBI, CIA, Secret Service and other executive personnel to conduct surveillance, illegally obtain IRS records, initiate discriminatory tax audits, and harass political opponents and activists.

The existence of the tape recordings turned allegations into fact, proving obstruction of justice and abuse of power. Facing almost certain removal from office, Nixon chose to resign on August 9, 1974, addressing the nation on television the night before.

“By taking this action, I hope that I will have hastened the start of the process of healing which is so desperately needed in America,” he said, adding, “I deeply regret any injuries that may have been done in the course of the events that led to this decision.”

In a final speech to White House staff, Nixon tearfully declared, “Those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself,” wisdom perhaps too bleak for a fortune cookie but well-suited to an unemployable despot.

A total of 69 people were charged with crimes; 48 people and 20 corporations eventually pled guilty. Twenty-five were sent to prison, among them many who had been top officials in Nixon’s administration. President Richard Nixon was, of course, pardoned by his successor Gerald Ford on September 8, 1974, whose decision may have helped cost him the 1976 election. It seems that the hatred of which Nixon spoke destroyed others as well.

*****

We hope you will pardon us for going into so much depth while still only scratching the surface of this issue. We always come back to the same question: Why did this guy get a library?

![]()

© 2017 – 2022, Worldwide Weird Holidays. All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!