February 2 is Sled Dog Day

Today is Sled Dog Day which recognizes the heroism of 20 men and 150 dogs who raced to save the town of Nome, Alaska from an epidemic. In January of 1925, children began to fall ill, gasping for breath. At least four died. Diphtheria is a highly contagious respiratory disease, often lethal without treatment. It’s curable, but the nearest supply of antitoxin serum was in Anchorage, 1,000 miles away.

On January 25th the town’s only doctor, Dr. Welch, arranged for the serum to be transported by train to Nenana, the end of the line, still almost 700 miles away. Experienced dogsledders, called mushers, decided to run their teams in relays to deliver the 20-pound batch of serum, wrapped in fur, to Nome.

The serum arrived in Nenana on the evening of January 27th. Musher “Wild Bill” Shannon tied the package to his sled and set off on the first 52-mile leg of a 674-mile journey that became known as the “Great Race of Mercy.” Wind chill reached -60° Fahrenheit.

The teams averaged six miles per hour and covered about 30 miles of ground apiece, but when Leonhard Seppala, a famous musher at the time, received the serum on January 31st in Shaktoolik, he covered 91 miles with lead dog Togo. He then handed it off to Charlie Olson, who traveled 25 miles before giving it to Gunnar Kaasen for what was supposed to be the second-to-last leg of the relay.

Kaasen ran straight into a blizzard, the snow sometimes so intense it caused a white-out in which he couldn’t see any of his 13-dog team. He trusted his lead dog, Balto, who relied on scent to guide them. At one point the sled flipped, pitching the serum into a snowbank and sending Kaasen scrambling to find it.

He arrived in Port Safety in the early morning hours of February 2nd, but when the next team was not ready to leave, he pressed on to Nome himself. At 5:30 AM, Balto led the way into Nome to deliver the serum, frozen solid, to Dr. Welch. The doctor thawed the antitoxin, then injected the townspeople. Three weeks later, he lifted the quarantine.

The relay had taken five-and-a-half days, cutting the previous record by almost half. Many mushers had suffered frostbite and four of the dogs died from exposure.

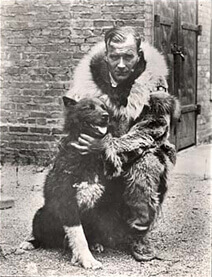

The story got international attention and Balto became a superstar. Within weeks, he was contracted to star in a short Hollywood film entitled Balto’s Race to Nome. After traveling to Seattle, Washington and shooting on Mt. Rainier, Kaasen, his wife, Balto and the rest of the team embarked on a nine-month vaudeville tour of the country. They arrived in December of 1925 to witness the unveiling of a bronze likeness of Balto in New York City’s Central Park.

The statue is located on the main path leading north from the Tisch Children’s Zoo. In front of it, a slate plaque depicts Balto’s sled team, and bears the following inscription:

Dedicated to the indomitable spirit of the sled dogs that relayed antitoxin six hundred miles

over rough ice, across treacherous waters, through Arctic blizzards from Nenana

to the relief of stricken Nome in the Winter of 1925.

Endurance · Fidelity · Intelligence

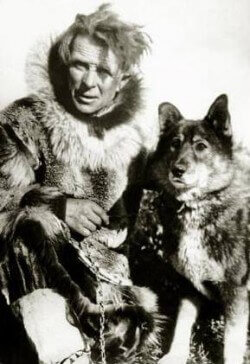

Although Seppala also toured the country and appeared with Togo in an advertising campaign for Lucky Strike cigarettes, he felt cheated by the attention lavished on Kaasen and Balto. He had raised Balto and considered him genetically inferior, with a boxy build; he’d neutered him as a puppy to ensure his line would not continue.

A quote from biography Seppala: Alaskan Dog Driver reads, “The chief thing which disturbed me was that Togo’s records were given to Balto, a scrub dog who was pushed into the limelight and made immortal. It was almost more than I could bear when the ‘newspaper’ dog Balto received a statue for his ‘glorious achievements.'”

The timing and circumstances surrounding what happened next is unclear. Both men worked for Pioneer Mining and Ditch Company near Nome. Kaasen was recalled by the company, most likely at his superior Seppala’s behest. Some accounts say Seppala’s friend, mountaineer Roald Amundsen confronted Kaasen in Chicago, Illinois, a stop on the vaudeville tour he’d been forced to resume due to financial difficulties, and told him to return home immediately. With Kaasen in Alaska, there would be nothing to divert attention from a ceremony Seppala had planned in which Amundsen would award a gold medal to Togo.

No matter how it came to pass, Kaasen found himself financially unable to secure passage for the dogs and with no time to raise funds. He had no choice but to leave them with the tour’s promoter, who had no use for 13 dogs and sold them at a stop in Los Angeles, California to a “museum” where they were tied up in a small dark room, neglected and sometimes abused. For a dime, people could peek in the room’s one small window and see the hero dogs that had saved a town.

This went on for several months until businessman George Kimble, visiting from Cleveland, Ohio, saw an advertisement for the attraction and went to have a look. Incensed at their deplorable condition, fearing that they would soon pine away and die, he approached the owner who offered to sell them to him for $2,000.

Mr. Kimble worked together with a Cleveland newspaper, The Plain Dealer, to get the word out. Children and adults all over the country donated and in only ten days, Kimble was able to rescue the dogs and bring them to Cleveland. (At this point, only seven dogs remained. It’s unknown what happened to the other six.) On March 19, 1927, Balto and his teammates received a hero’s welcome in a triumphant parade. The dogs were then taken to the Brookside Zoo and lived the rest of their lives in comfort.

After Balto died in 1933, his remains were mounted by a taxidermist and donated to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. In 1998, the Alaska legislature passed HJR 62- the ‘Bring Back Balto’ resolution. The museum refused to return Balto but in October of that year, they loaned him for five months to the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, which drew record crowds.

After Togo’s death in 1929, Seppala had him custom mounted and displayed at Yale University’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. (His skeleton is still there.) In 1964, the stuffed dog was transferred to a museum in Vermont.

During all the years he was displayed, Togo was not enclosed. His coat had begun to bald where he was petted. His significance forgotten, Togo was put into storage in 1979. A carpenter who happened to have a background in racing sled dogs discovered him in 1983 atop an old refrigerator.

The sled run of 1925 became international news again. The museum was pressured by legislators, dog clubs, and museums to do something, whether it was to try to repair the taxidermy, bury him where he had died or, as a letter-writing campaign begun by Alaskan schoolchildren urged, return him to the place of his greatest triumph.

Today he is on display in a glass case at the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race Headquarters Museum in Wasilla, Alaska.

Raise a glass to Balto and Togo and all the dogs that save lives or just make our lives better. Hear, hear and have a happy Sled Dog Day!

![]()

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!