February 10 is Plimsoll Day

Today is Plimsoll Day. It celebrates the birth of Samuel Plimsoll (Feb. 10, 1824— June 3, 1898), a British merchant, politician, author and reformer whose tireless efforts saved many sailors’ lives.

Plimsoll realized that the power to bring ship owners to account rested with the government. So he ran for a seat as a member of Parliament (MP) and was elected on the second try, in 1868. He tried in vain for the next eight years to pass a bill to regulate the shipping industry.

Sinkings occurred so frequently that the term “coffin ship,” overloaded, unseaworthy vessels, often so heavily insured that shipping companies stood to make a higher profit if the ship sank. Plimsoll sought to end this by advocating the inspection of all vessels, adoption of a maximum load line and limitation of insurance according to proportions of property on any one ship.

Plimsoll also fought the 1871 Merchant Shipping Act, which obligated seamen to complete a voyage after they had signed a contract. Any sailor who realized a ship was unseaworthy before boarding or during the journey was subject to imprisonment if he refused to go on.

It wasn’t unusual for a company to paint over wood rot, rename a ship and present it as new. When heavy loads were added, a ship could sink in anything but perfect weather. In March 1873, The Times printed a story about fifteen seamen who were imprisoned for months after they refused to board a ship. When the ship finally set sail with a new crew, it sank and three men drowned.

That year, Plimsoll published Our Seamen: An Appeal, a powerful attack on ship owners who knowingly risked their crews’ lives for their own profit. It brought public attention to the injust treatment of working men and incensed many MPs, especially those who were ship owners. (Plimsoll had arranged to have a copy of his book placed on each member’s seat in the House of Commons.)

Some decried him as a militant and tried to have him drummed out of Parliament. But Plimsoll had momentum and public support, although he would later nearly drum himself out. He initiated a Royal Commission to investigate wrongdoing and two years later in 1875, a bill was introduced. It was inadequate, in his opinion, and left ample room for amendments to further weaken it in the future.

However, it was better than nothing and Plimsoll made the difficult decision to support it. Parliament met on July 22, 1875, to ratify the bill. Then Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli changed his mind, deciding not to bring it to a vote, essentially killing it.

Plimsoll had labored for years to force companies to value safety over greed. When Disraeli appeared to accede to the wishes of his enemies, Plimsoll jumped from his seat in a rage, bounded to the floor in front of Speaker Sir Henry Brand and shook his fist at both sides of the assembly.

He proceeded to name-drop MP Edward Bates as the owner of three ships that had sunk the year before, killing 87. He stated that he intended to name others. Here’s the transcript of what happened next:

MR. PLIMSOLL: I am determined to unmask the villains who send to death and destruction—[Loud cries of “Order!” and much excitement.]

MR. SPEAKER: The hon. Member makes use of the word “villains.” I presume that the hon. Gentleman does not apply that expression to any Member of this House.

MR. PLIMSOLL: I beg pardon?

MR. SPEAKER: The hon. Member made use of the word “villains.” I trust he did not use it with reference to any Member of this House.

MR. PLIMSOLL: I did, Sir, and I do not mean to withdraw it. [Loud cries of” Order!”]

MR. SPEAKER: The expression of the hon. Member is altogether un-Parliamentary, and I must again ask him whether he persists in using it.

MR. PLIMSOLL: And I must again decline to retract. [“Order!”]

MR. SPEAKER: Does the hon. Member withdraw the expression?

MR. PLIMSOLL: No, I do not.

MR. SPEAKER: I must again call upon the hon. Member to withdraw the expression.

MR. PLIMSOLL: I will not.

This went on until Plimsoll was asked to withdraw. He pretended not to hear, then stated, “I will withdraw,” thankfully ending the exchange before the inevitable “I know you are but what am I” stage and the ritual sticking out of tongues.

Disraeli moved to issue an immediate reprimand but MPs friendly with Plimsoll made the case that he had been overwrought by the burden of trying to save lives and would come to his senses soon. The prime minister agreed to a weeklong timeout instead.

Eventually, Plimsoll did apologize. Many people believed that the government had buckled under pressure from ship owners; they, in turn, pushed Disraeli to reverse his position and pass the bill. In 1876, the Merchant Shipping Act became law. Amendments limiting liability were finally repealed in 1894. Foreign ships visiting British ports were required to have a load line as of 1906.

Plimsoll remained a public servant for many more years, He was honorary president of the National Amalgamated Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union for several years and wrote a book about the horrible conditions cattle suffered during shipping. He even traveled to the U.S. to encourage a less negative portrayal of England in textbooks. He died on June 3, 1898.

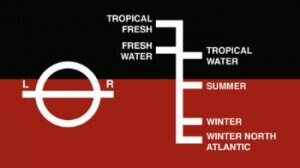

He will forever be remembered for his creation of the loading line that came to be known as the Plimsoll Line, marked on the hull of every cargo ship, indicating the maximum depth to which the ship can be safely loaded.

It’s impossible to estimate the number of sailor’s lives that have been saved because of Plimsoll’s dogged determination. A statistic attributed to Royal Museums Greenwich sets the total number of British ships lost in 1873 and 1874 at 411, with a loss of 506 lives. An A-level physics textbook lists U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration as its source.

Neither site appears to have that quote. We are unable to track down the source of the number, which has been picked up and reported as fact like a Web-borne virus. It may very well be true but we can’t find confirmation in anything from accounts of the time to a 1981 thesis paper.(Nicely done, Mr. Dixon. We hope you received your PhD.)

It doesn’t really matter whether that number is correct; by any metric, the Plimsoll line has saved thousands in the intervening years. In 1929, the National Union of Seamen erected a monument in his honor, in grateful recognition of his services to the men of the sea of all nations. It stands on the Victoria Embankment in London, overlooking the Thames River.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!