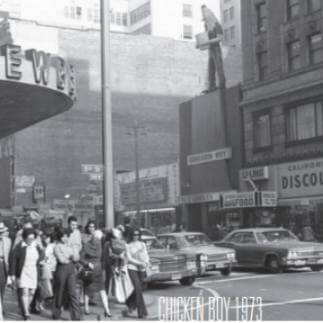

Today is Chicken Boy Day, celebrating the birthday of the fiberglass legend on September 1, 1969, or thereabouts. Official birth records are unavailable.

Twenty-two feet tall, referred to by many as the Statue of Liberty of Los Angeles, California, Chicken Boy stood atop his namesake restaurant on Broadway between Fourth & Fifth Streets for fourteen years, betraying no emotion regarding the dismembered, fried fowl that presumably filled the golden bucket he held before him.

When the restaurant closed in the autumn of 1983, Chicken Boy awaited a fate similar to that of his flesh-covered counterparts: mechanical separation followed by the discarding of his skeletal remains. Artist Amy Inouye, who had grown fond of the landmark since her move to Los Angeles in the 1970s, decided to save him.

While the owners may have been unsure of her sanity, they were persuaded by her sincerity. With permission secured, she made many calls to moving companies that started, “Can I get an estimate to dismantle and move a 22-foot-tall fiberglass statue of a man with a chicken’s head, also known as Chicken Boy?” Eventually, she convinced one that she was not making a prank call and the move was scheduled.

On May 4, 1984, Chicken Boy was removed and taken to the first of many storage facilities. Inouye sent letters to several museums, certain they would want to include the Los Angeles icon in their sculpture gardens. Only one or two responded that Chicken Boy was a sign and therefore did not qualify as art.

Inouye began to sell Chicken Boy t-shirts, then lapel pins, pens and mugs, among other things. She put together a souvenir catalog. The proceeds helped pay for storage. At its zenith, her mailing list boasted 14,000 names.

Of the phenomenon, Inouye says, “The legend of Chicken Boy grew far beyond downtown LA—it became obvious that his appeal was universal. In every person, it seems, there is a little or a lot of self-conscious awkwardness trying to accept those cards they were dealt—we are, in fact, all Chicken Boy.”

Despite mentions in Newsweek, Esquire, the San Francisco Chronicle, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and the Los Angeles Times, air time on countless radio shows and a brief viewing at the underground Arco Plaza mall, Chicken Boy had no place to call his own.

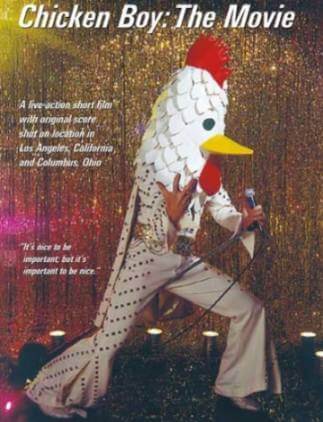

In a film called Chicken Boy: the Movie, he comes alive due to the Harmonic Convergence of 1987, a Mayan/Hell/astrological alignment/power center prophesy even less believable than a fiberglass statue receiving the breath of life and learning to play the accordion.

In early 2007, Inouye found a small office building in Highland Park where she could run a small art gallery while Chicken Boy watched over Route 66 from his rooftop perch. The neighborhood of artists and musicians welcomed them both. She applied for and received a Community Beautification Grant.

Then, after eight months spent navigating the permit process, Chicken Boy was hoisted to his new roost atop Future Studio at 5558 North Figueroa Street. On October 18, 2007, after twenty-three years, five months and fourteen days, Chicken Boy was finally home.

Mel Brooks once said, “The whole word chicken is funny. The ch, the i, the k, put it all together, youʼve got the funniest word in the English language.” Maybe that explains the appeal of Chicken Boy. It definitely explains why we’ve used the word seventeen times.

Happy Chicken Boy Day! (Whoops, eighteen!)

![]()

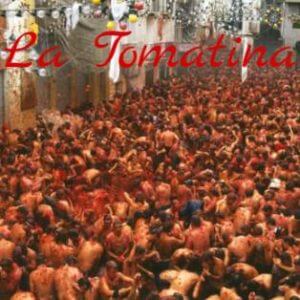

Today is La Tomatina, a legendary festival held on the last Wednesday of August in the Spanish town of Buñol.

Today is La Tomatina, a legendary festival held on the last Wednesday of August in the Spanish town of Buñol.