September 9 is Tester’s Day

Today is Tester’s Day. This unofficial holiday for technicians everywhere is not without controversy.

The Story

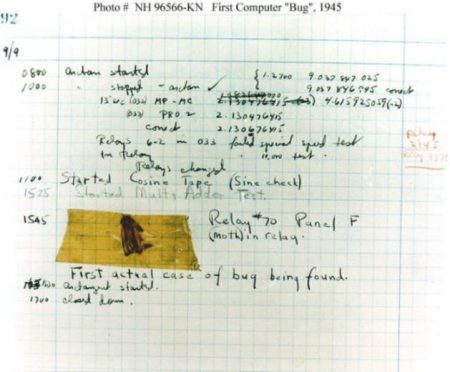

On September 9, 1945, Grace Hopper, a computer scientist at Harvard University, was running tests on the Mark II Calculator (designed by Howard Aiken) when she found a moth that had landed between two solenoid contacts, shorting out an electromechanical relay.

Hopper removed the squashed bug—no one knows if she dispatched it herself—and taped it to the project’s logbook with the notation: “First actual case of bug being found.” Hopper had carried out the first “debugging” and coined the term that would become synonymous with the identification and elimination of the frustrating glitches that cause computers to malfunction.

Flies in the Ointment

This story doesn’t pass muster for a few reasons.

1. The Mark II came online in 1947, two years later. That’s easy enough to explain: looking at the photo of the logbook, anyone can see that the time and date are included, but not the year. Fix that and the story’s hunky dory, right? Not really.

2. Hopper’s own description indicates that she didn’t invent the usage of “bug.” “First actual case of bug” [emphasis ours] implies that the term was already in use in a figurative sense. Nitpicky? Perhaps. The usage can be traced back at least as far as 1878, when Thomas Edison used the word in a letter to Theodore Puskas, a fellow inventor.

“‘Bugs’ — as such little faults and difficulties are called — show themselves and months of intense watching, study and labor are requisite before commercial success or failure is certainly reached.”

The meaning was also included in Webster’s Second International Dictionary, published in 1934. Okay, maybe Hopper wasn’t the first person to call a glitch a “bug.” But didn’t she find that moth, whether it was in 1945 or 1947? Probably not.

3. In 2007, the Smithsonian Institution honored the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the bug. Curator Peggy Kidwell, who included the logbook page in the exhibit, noticed that the notation wasn’t made in Hopper’s handwriting.

Ingrid Newkirk, director of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), objected to the display, urging people not to use animals’ names as pejoratives, stating:

“We discourage people from saying things like ‘kill two birds with one stone.’ The manner in which we’ve been taught to think of animals is mostly negative. We need to be more respectful.”

PETA is concerned about the defamation of insects, an important part of our ecosystem. So Newkirk is essentially telling the Smithsonian, “You give bugs a bad name.” We imagine her leaving the museum to deliver a speech touting all the good things about, say, hookworms. They probably don’t get enough good press.

Amazing Grace

In our opinion, none of the nonsense above detracts from the accomplishments of Grace Hopper. In 1943, she left her job teaching mathematics at Vassar College to join the Navy. She was turned down but was admitted to the Naval Reserve after receiving special permission: She weighed 15 pounds less than the Navy’s 120-pound minimum.

After the war, she helped program the Mark I, predecessor to the Mark II of bug fame. She co-authored three papers about the computer, also known as the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, with designer Howard Aiken.

She later joined the group building the UNIVAC I. In 1952, she invented the first compiler, for use with the A-O computer language, but had difficulty convincing anyone it would work. “I had a running compiler and nobody would touch it,” she said later.”They told me computers could only do arithmetic.” Ultimately she prevailed and was given her own team, which produced programming languages MATH-MATIC and FLOW-MATIC.

In 1959, Hopper served as a technical consultant to the committee that defined the new language COmmon Business-Oriented Language (COBOL). Her conviction that programs should be written in a language resembling English, rather than machine code, helped COBOL go on to be the most-used business language in history.

In 1967, she was named the director of the Navy Programming Languages Group, developing software and a compiler as part of the COBOL standardization program for the entire Navy.

She reached the rank of Rear Admiral in 1985. The following year, she was forced to retire after having remained on active duty many years beyond mandatory retirement age by special permission of Congress. At a ceremony held on the USS Constitution, Hopper received the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, the highest non-combat-related honor awarded by the Department of Defense.

She also wrote several programming books and lectured until her death on January 1, 1992, at the age of 85. She was buried with full military honors at Arlington Cemetery. The Navy’s Arleigh Burke-class missile destroyer USS Hopper (DDG-70) is named for her, as is the Cray XE6 “Hopper” supercomputer at The National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center.

She once said:

“The most important thing I’ve accomplished, other than building the compiler, is training young people. They come to me, you know, and say, ‘Do you think we can do this?’ I say, ‘Try it.’ And I back ’em up. They need that. I keep track of them as they get older and I stir ’em up at intervals so they don’t forget to take chances.”

Thank you, Grace. We don’t give a hoot whether you found that silly—sorry, PETA, we mean noble—bug or not!

Update

In 1933, Yale University named a residential college after John C. Calhoun, an 1804 graduate who was an enthusiastic supporter of slavery. In 2017, after years of pressure, protests and vandalism of artwork depicting slaves, the university changed the name from Calhoun to Grace Hopper College. (She earned her Ph.D. in mathematics at Yale in 1934.) Although it has nothing to do with Tester’s Day, we mention it because it brings attention to Hopper’s accomplishments.

Happy Tester’s Day!

![]()