May 1 is Law Day

Today is Law Day, created in 1957 by American Bar Association (ABA) president Charles S. Rhyne. The following year, President Dwight D. Eisenhower established Law Day to honor the U.S. legal system. Each year, the sitting president signs a new proclamation. In 1961, Congress issued a joint resolution designating May 1st as the official date for celebrating Law Day.

Today is Law Day, created in 1957 by American Bar Association (ABA) president Charles S. Rhyne. The following year, President Dwight D. Eisenhower established Law Day to honor the U.S. legal system. Each year, the sitting president signs a new proclamation. In 1961, Congress issued a joint resolution designating May 1st as the official date for celebrating Law Day.

The ABA sponsors educational programs on Law Day. The theme for 2016’s 50th anniversary was “Miranda: More Than Words,” referencing the June 13, 1966, decision by the Supreme Court that anyone in police custody must be explicitly informed of his or her right to remain silent and refrain from making self-incriminating statements before being interrogated.

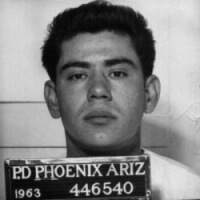

In 1963, 23-year-old laborer Ernesto Miranda was arrested in Arizona for the kidnapping and rape of a cognitively-impaired teenaged girl. After two hours of intense questioning, he said he had committed the crime and wrote his confession on paper provided to him by the police. The following words were already printed across the top of each sheet: “This statement has been made voluntarily and of my own free will, with no threats, coercion or promises of immunity and with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding any statement I make can and will be used against me.”

Miranda hadn’t been told he had a right to an attorney and had no idea he didn’t have to answer the police’s questions. He recanted. Alvin Moore, the lawyer later assigned his case, argued that the confession was illegally obtained and should be excluded from evidence. Moore’s objections were overruled; on the basis of the confession, Miranda was convicted and sentenced to 20 to 30 years. He appealed to the state’s Supreme Court but the conviction was upheld.

When Moore was unable to continue due to medical reasons, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) turned to the law firm of Lewis & Roca in Phoenix, Arizona, to represent Miranda. Criminal defense attorneys John J. Flynn, John P. Frank, Paul G. Ulrich and Robert A. Jensen worked pro bono, drafting and submitting a 2,500-word petition to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In November 1965, the court agreed to hear the case. Seven months later, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the opinion in Miranda v. Arizona, which concluded that:

The person in custody must, prior to interrogation, be clearly informed that he has the right to remain silent, and that anything he says will be used against him in court; he must be clearly informed that he has the right to consult with a lawyer and to have the lawyer with him during interrogation, and that, if he is indigent, a lawyer will be appointed to represent him.

The judgment didn’t mention Miranda, but the wording that evolved became known as the Miranda Warning and the verb Mirandize entered the lexicon. In 1968, the warning’s text was finalized by California deputy attorney general Doris Maier and district attorney Harold Berliner. It reads:

You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you. Do you understand the rights I have just read to you? With these rights in mind, do you wish to speak to me?

The ABA provides more detail on its website:

The purpose of the Miranda Warning is to ensure the accused are aware of, and reminded of, these rights under the U.S. Constitution, and that they know they can invoke them at any time during the interrogation. Miranda Rights are given under circumstances of “custody” and “interrogation.”

• Custody means formal arrest or the deprivation of freedom to an extent associated with formal arrest.

• Interrogation means explicit questioning or actions that are reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response.

• Contrary to what is depicted on many television shows, the police do not need to give the Miranda Warnings before making an arrest. But the warning must be given before interrogating a person while in custody.

Ernesto Miranda’s conviction was overturned but he did not go free. He was tried again using witnesses and other evidence and convicted. After he was granted parole in 1972, he made money autographing the Miranda Warning cards that police were required to carry and recite to suspects. He was arrested for several driving offenses and lost his license. In 1975, he was arrested for possession of a firearm, in violation of his parole. He was sent back to prison for a year. On January 31, 1976, after his release, he got into a bar fight and was stabbed to death.

On June 17, 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in Salinas v. Texas that it is not enough to remain silent. Justice Samuel Alito said that the privilege against self-incrimination must be expressly invoked or a prosecutor could use a suspect’s silence against him. Justices Clarence Thomas and Antonin Scalia stated that they concurred but would have gone further and overruled the 1965 Griffin v. California judgment, in which the Supreme Court decided that the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination prohibits a prosecutor or judge from negatively commenting on a defendant’s failure to testify.

Shouldn’t the warning be updated? “You have the right to remain silent but only if you tell us first.” If you don’t answer because you don’t understand or because, frankly, it’s so ironic it sounds like a trick question, does that mean you have waived your rights? It’s like getting tagged out in the schoolyard (“You didn’t say ‘Olly, olly, oxen free‘!”) except in this case you may go to prison for not saying the magic words.

Know your rights, protect those rights and have a safe and happy Law Day!

![]()

Today is 2016’s International Virtual Assistants Day (IVAD), which honors the support staff who will never hit on a coworker, pass gas in the conference room or steal someone else’s yogurt from the company fridge. It takes place on the third Friday of May, during the Online International Virtual Assistants Convention (OIVAC).

Today is 2016’s International Virtual Assistants Day (IVAD), which honors the support staff who will never hit on a coworker, pass gas in the conference room or steal someone else’s yogurt from the company fridge. It takes place on the third Friday of May, during the Online International Virtual Assistants Convention (OIVAC). Today is National Blame Someone Else Day, celebrated on the first Friday the 13th of the year. According to almost every source we checked, the holiday was invented by Anne Moeller of Clio, Michigan in 1982.

Today is National Blame Someone Else Day, celebrated on the first Friday the 13th of the year. According to almost every source we checked, the holiday was invented by Anne Moeller of Clio, Michigan in 1982.