May 2 is Tuatara Day

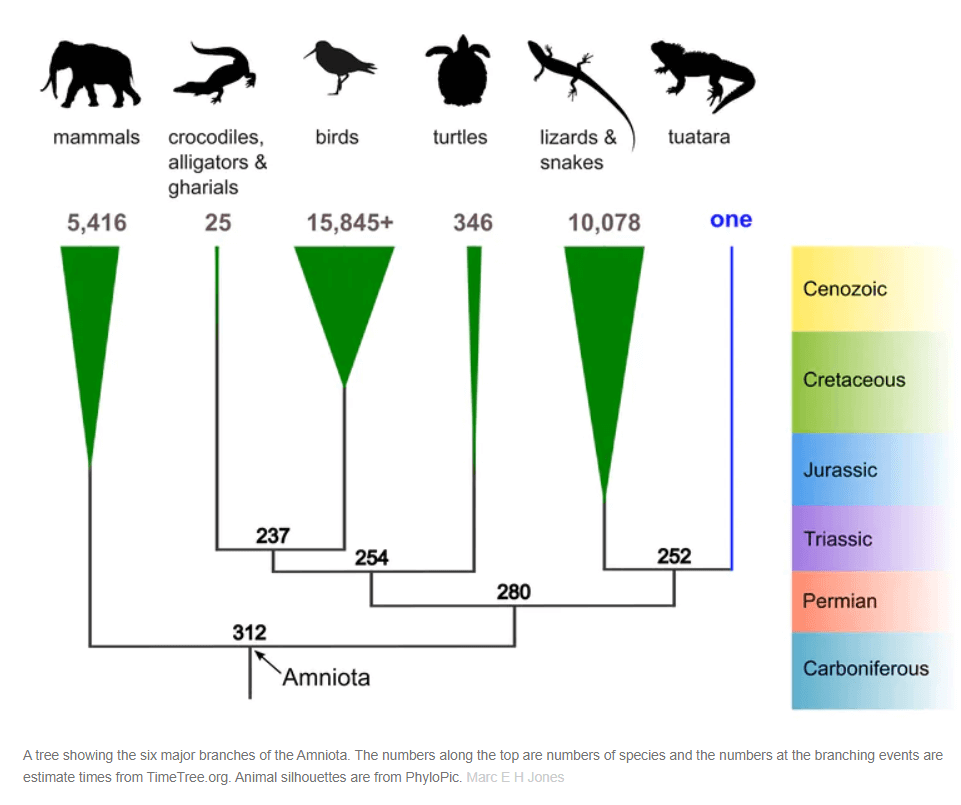

Today is Tuatara Day. On May 2, 1867, scientists first recognized that the tuatara, a reptile found only in New Zealand, is not a lizard (Squamata) as originally thought. Why is this important? Like Tigger and the Highlander, there can be only one. The tuatara is the sole surviving representative of its own group (Rhynchocephalia), which existed alongside dinosaurs.

Although Rhyncocephalia is the closest living relative of Squamata, which includes both lizards and snakes, the two groups diverged about 250 million years ago. To put that family relationship into perspective, a human is more closely related to, say, a kangaroo, than the tuatara is to a lizard.

Tuatara is a Māori name meaning “peaks on the back,” a reference to its spiny crest, and the species has been identified by the Māori people as a taonga (treasure). It is nocturnally active and spends its days basking in the sun or in a burrow. Although capable of digging the burrow itself, it prefers to use those made by birds.

Unlike a lizard, it has two rows of teeth on the top, which are fused to the jawbone. When feeding, the bottom row bites between the upper rows of teeth, then slides forward in a shearing motion that allows it to decapitate its prey, as evidenced by reports of birds’ headless bodies found outside their lairs. Not a nice way to treat one’s landlord, certainly.

Tuatara reach sexual maturity around age 14 and have been known to live up to 70 years in the wild and much longer in captivity. The male’s lack of external genitalia makes it useful to research into the evolution of the phallus in amniotes (mammals, birds, and reptiles). Because females only breed every two to five years, producing six to ten eggs that require incubation for up to a year, population numbers are low and protected, making it nearly impossible to obtain embryos for study.

In 2015, researchers used 3-D technology to virtually reconstruct an embryo from slides that had been prepared in 1909 and left in a collection at Harvard University ever since. Their finding that the embryo possessed genital buds suggests a single evolutionary origin of amniote external genitalia. As researcher Thomas J. Sanger wrote, “Without access to these museum specimens we would have no way of knowing the secrets of the tuatara penis.” Author’s note: As a layperson, while I found the subject fascinating, I began to feel I was, at the very least, invading the tuatara’s privacy, and at worst, straying into reptile porn territory. I’m pretty sure my Google search history has been flagged.

Once plentiful, tuatara numbers have decreased since the arrival of humans, dogs, and Pacific rats about 800 years ago. Rats, in particular, have decimated the number of tuatara, most likely due to competition for food and/or predation on eggs and juveniles. Rats, as well as possums and stoats, are being exterminated as part of a government initiative called Predator Free 2050 to save the tuatara and other native species from extinction. The cat, another introduced species, has apparently been exempted from the culling thus far. PETA remains strangely silent on New Zealand’s rodenticide.

Climate change is another threat to the tuatara, who exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination. The warmer an egg’s environment, the more likely the hatchling will be male. As temperatures rise, conservationists are taking steps, such as carefully relocating tuatara to milder areas to keep the ratio from skewing so male that the population collapses.

Although Tuatara Day was first celebrated in 2017 on the 150th anniversary of the scientists’ recognition, boasting its own hashtag, #150NotALizard, on social media, one tuatara had been making headlines since 2009. That’s when Henry, a tuatara living at New Zealand’s Southland Museum, achieved celebrity status after becoming a first-time parent at the ripe old age of 111.

His mate Mildred, a tuatara in her seventies, had apparently forgiven Henry for their disastrous first date 25 years earlier when he’d bitten off her tail, and she seemed unconcerned by their age difference. (We don’t like to use the phrase “robbing the cradle” since tuatara sometimes eat their young. It’s a bit of a sore subject.) Mildred laid 12 eggs and on January 25, 2009, after 223 days of incubation, 11 baby tuatara hatched.

Seven years later, Henry met Prince Harry on the then royal’s tour of New Zealand. There’s no mention of whether Mildred and the kids were in attendance, too. I was able to reach David Dudfield, Curator Manager at Southland Museum, who let me know that Henry is still going strong and recently celebrated the 50th anniversary of his arrival there. He and Mildred have had so many more babies that the randy couple has been separated while staff work to find homes in the wild for some of their offspring.

No word on how he feels about Megxit.

Happy Tuatara Day!

![]()

Sources:

Tuatara – Current Biology, Volume 22, Issue 23

Evolution: One Penis After All – Current Biology, Volume 26, Issue 1

Not a lizard nor a dinosaur, tuatara is the sole survivor of a once-widespread reptile group – The Conversation

Reproduction of a Rare New Zealand Reptile, the Tuatara Sphenodon punctatus, on Rat‐Free and Rat‐Inhabited Islands – The Society for Conservation Biology

Resurrecting embryos of the tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus, to resolve vertebrate phallus evolution – Royal Society

Predator Free 2050 – New Zealand Department of Conservation

Predator Free 2050: New Zealand ramps up plan to purge all pests – BBC News

When a species can’t stand the heat – Science News for Students

Henry the tuatara is a dad at 111 – The Independent

Prince Harry strokes 118 year-old Tuatara reptile en route to New Zealand’s Stewart Island – The Telegraph

Today is Speak in Complete Sentences Day. Celebrating this holiday may prove more difficult than you’d think.

Today is Speak in Complete Sentences Day. Celebrating this holiday may prove more difficult than you’d think. 1. the blossom of a plant

1. the blossom of a plant Today is Put a Pillow on Your Fridge Day, a new take on an old tradition.

Today is Put a Pillow on Your Fridge Day, a new take on an old tradition.