June 1st is Heimlich Maneuver Day. In 1974, the journal Emergency Medicine published Dr. Henry Heimlich’s invention of a method to combat choking that has saved countless lives.

At the time, a series of blows to the back was the treatment of choice. Thoracic surgeon Heimlich set out to find a better way. He realized that when choking, air is trapped in the lungs. When the diaphragm is elevated, the air is compressed and forced out along with the obstruction.

He anesthetized a beagle to the verge of unconsciousness, plugged its throat with a tube, then conducted experiments to find an easy way to get the dog to expel it. After succeeding, he reproduced the result with three other beagles.

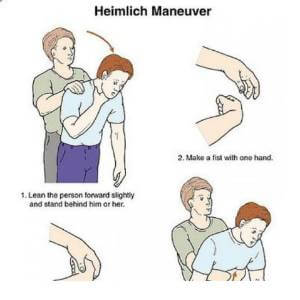

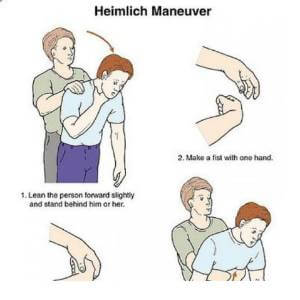

Refined for use on humans, his technique entails standing behind the choking person, making a fist below the sternum but above the belly button and pulling it in and up to dislodge the blockage.

In 1976, the Heimlich maneuver became a secondary procedure to be used only if back blows were unsuccessful. In 1986, the American Heart Association (AHA) changed its guidelines, instituting the Heimlich maneuver as the only option for rescuers.

Although Heimlich is also a fierce proponent of using the procedure to rescue drowning victims, the AHA warns it can lead to vomiting, aspiration pneumonia and death.

But his most controversial theory is “malariatherapy,” the practice of infecting a patient with malaria to treat another ailment. Although he had no expertise in oncology, Heimlich was convinced it could treat cancer.

In 1987, after the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) refused to supply him with infected blood, he went to Mexico City and convinced the Mexican National Cancer Institute (MNCI) to allow him to treat five patients with malariatherapy. Four of the patients died within a year. The project was abandoned with no follow-up studies.

In 1990, The New England Journal of Medicine published Heimlich’s letter proposing malariatherapy as a Lyme disease treatment. Before long, sufferers around the world began to ask for the treatment. But lack of supporting evidence and poor patient reviews spelled the end of the exercise.

Within a few years, he decided it could tackle AIDS. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), labeled the idea “quite dangerous and scientifically unsound.” But Heimlich was able to secure financing from Hollywood donors and set up a clinic in China.

In 1994, his Heimlich Institute paid four Chinese doctors between $5,000 and $10,000 per patient to inject at least eight HIV patients with malarial blood. At the 1996 International Conference on AIDS, he announced that in two Chinese patients, CD4 counts that decrease as HIV progresses to AIDS, had increased after malariatherapy and remained elevated two years later.

When experts reviewed the studies, they discovered that the test the Chinese doctors used to measure CD4 levels was notoriously unreliable, rendering the results useless. Heimlich pressed on but had a difficult time finding sponsors.

In 2005, Heimlich determined a re-branding was in order; reasoning that the word “malaria” might scare people off, he changed the name to immunotherapy. When speaking to a journalist, he refused to disclose the exact location of his latest clinical trial in Africa. Due to its ethically dubious practice of initially denying treatment for malaria, the study has been conducted without governmental permission.

The same year, the AHA did a little de-branding: its guidelines no longer refer to the Heimlich maneuver by name. It is now simply called an “abdominal thrust.” Since 2001, an anonymous campaign has sought to label Heimlich a fraud and expose alleged human rights abuses in connection with his experimentation on unwilling participants. Heimlich’s accuser was his son Peter.

On Monday, May 23, 2016, the 96-year-old performed his maneuver on 80-year-old Patty Ris, a fellow resident at Deupree House, a senior living community in Cincinnati, Ohio. He told a reporter it was the first time he’d used his invention to save a life. (In 2003, he told BBC Online News that he’d saved someone at a restaurant three years earlier.) Heimlich died on December 17, 2016, after suffering a heart attack.

While Dr. Henry Heimlich may have been a complicated individual, there’s no denying that he created a life-saving procedure. He didn’t do it alone, according to Dr. Edward Patrick, an emergency room physician who said he helped develop it before Heimlich took sole credit and slapped his name on it. Even Peter doesn’t believe Patrick’s story, but we have to admit it’s hard to know what’s true and what’s false.

Happy Heimlich Maneuver Day!

![]()

June 25, 2016, is the World Championship Rotary Tiller Race, the main event of the

June 25, 2016, is the World Championship Rotary Tiller Race, the main event of the