January 17 is Palomares Hydrogen Bomb Accident Day

Palomares Hydrogen Bomb Accident Day

January 17, 2016, marked the fiftieth anniversary of the worst nuclear accident you’ve probably never heard of, which took place over and on Palomares, Spain, and its 2,000 inhabitants. Its effects are still being discovered and its dangers are evolving as plutonium, with a half-life of 24,000 years, continues to contaminate the town and its people, plants and animals.

On January 17, 1966, the Cold War was in full swing and the US Air Force was on continuous airborne alert, flying routes across the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea to points along the border of the Soviet Union. The lengthy flights required two mid-air refuelings.

A B-52 carrying four hydrogen bombs collided with its refueling plane, killing seven airmen and dropping its bombs. Conventional explosives in two detonated on impact, scattering radioactive plutonium over the farming town of Palomares.

Luckily—luck being a relative thing—the warheads were unarmed, preventing thermonuclear explosions, each of which would have been 73 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb.

The story most of the world heard was that one bomb had fallen and was eventually retrieved intact from the water eighty days later. The search for that bomb overshadowed the calamitous radioactive fallout that resulted. No one was evacuated from the village.

U.S. Ambassador Angier Duke told the press, “This area has gone through no public health hazard of any kind, and no trace whatsoever of radioactivity has ever been found.” On March 8, he (and tourism minister Manuel Fraga) took a much-publicized swim at a local beach to prove the water was safe. “If this is radioactivity,” he told reporters, “I love it!”

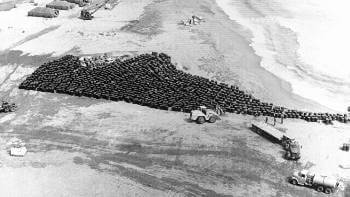

For three months, U.S. personnel and Spanish Civil Guards worked to decontaminate the area. Radioactive topsoil covering 5.4 acres was shoveled into thousands of barrels and shipped to the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina for processing. Land with lower surface contamination levels, totaling 42 acres, was plowed under to a depth of 12 inches.

Buildings were pressure-washed; those that still registered significant radiation were painted to cover the plutonium. Chipping, scraping, or sanding to repaint would, of course, reintroduce it into the atmosphere to be inhaled, ingested and absorbed.

Palomares was known for its delicious raf tomatoes. In 1966, all of them were burned (an action that dispersed more plutonium). After the cleanup, the next several crops failed but farmers persevered. They continue to grow them today, resentful that they have to sell them under a false name because of safety concerns about local produce.

It has never been officially acknowledged that the humans who grew those tomatoes should be worried about their own exposure to radiation. In 1971, Wright Langham, a scientist at Los Alamos Laboratories, visited Palomares to assess the monitoring program put in place post-cleanup.

He found that only 100 villagers had undergone lung and urine testing; 29 tested positive, but that number was deemed “statistically insignificant.” None of the participants were allowed access to their medical records until 1985, after the town’s mayor successfully agitated to have them released.

In 2006, radiation levels detected in snails and other wildlife indicated the presence of dangerous amounts of radioactive material underground. In April 2008, two trenches containing debris and contaminated earth were discovered near the crash sites. American troops dug them in 1966, most likely in a last-minute effort to complete the cleanup before the mission ended. The U.S. government denied any wrongdoing.

Even when the U.S. began making payments to Spain shortly after the accident to help monitor the aftermath, it took no responsibility for loss of life or livelihood, let alone poisoning the land. When the agreement lapsed in 2009, their payments stopped. A new deal between the two countries seemed unlikely.

That, at least, has changed. On October 19, 2015, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Spanish Foreign Minister José García-Margallo y Marfil signed a “statement of intent.” (full text here)

The United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain (hereinafter collectively the “Participants”) intend to cooperate in a program to further remediate the site of a radioactive accident near Palomares, Spain, and with that aim they intend to negotiate as soon as possible an agreement to establish the necessary activities, roles and responsibilities of each Participant in that remediation and disposal project.

When? Soon. Until then, here’s a fence to keep everyone safe. Happy 50th anniversary, Palomares Hydrogen Bomb Accident Day!

UPDATE:

On June 20, 2016, the New York Times ran an article about the American servicemen ordered to do cleanup at the site with no protective gear. After fifty years, government records have been declassified, showing systemic negligence toward the servicemen put in harm’s way.

When urine tests taken during the cleanup showed alarmingly high concentrations of plutonium, the Air Force threw out the results as “clearly unrealistic.” Although its own report recommended it, there was no effort to do follow-up tests and the Air Force has kept the radiation tests out of the men’s files.

The Department of Veterans Affairs relies on the Air Force’s records, which maintain that there was no harmful radiation in Palomares. The result? Veterans suffering multiple forms of cancer due to plutonium contamination are unable to receive full health care coverage; their claims are denied again and again.

Ronald R. Howell, 71, told the New York Times, “First they denied I was even there, then they denied there was any radiation.” Regarding a recent brain tumor removal, he said, “I submit a claim, and they deny. I submit appeal, and they deny. Now I’m all out of appeals. Pretty soon, we’ll all be dead and they will have succeeded at covering the whole thing up.”

![]()