Today is National Disc Jockey Day. It marks the death of legendary radio DJ Albert James “Alan” Freed (December 15, 1921 – January 20, 1965).

Freed’s radio career began in 1945 at WAKR in Akron, Ohio, where he played rhythm and blues (R&B) records. He moved to WJW Cleveland in 1951 and continued to champion music without regard to race, at a time when stations that targeted white listeners ignored black artists.

Freed began calling the music “rock and roll” because “it seemed to suggest the rolling, surging beat of the music.” The term was suggestive, already in use as slang for sex, but Freed was the first radio DJ to use it.

As his show’s popularity increased, Freed decided to stage a dance at the Cleveland Arena. Tickets to the “Moondog Coronation Ball” on March 21, 1952, sold out. Thousands more showed up to crash the party. Although the police shut it down early, it is considered by many historians as the first real rock concert.

In 1954, after a salary dispute, Freed moved to WINS New York and called his late-night show “Rock ‘n’ Roll Party.” The concerts he organized in New York and other cities began to draw white as well as black youth. Soon enough, Freed made enemies of the three Ps: parents, priests, and press. The Daily News labeled the music “an inciter of juvenile delinquency” and named Freed the chief instigator.

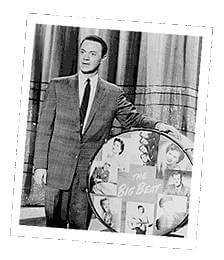

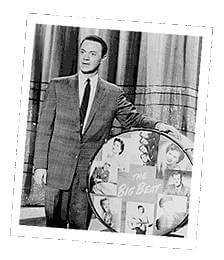

At first, this only increased his fame. WINS doubled his airtime; he began to get co-writing credits and royalties on the songs he played. He played himself in a series of musical films. In July of 1957, ABC hired Freed to host a TV show called The Big Beat but canceled it after the fourth episode showed a black singer dancing with a white girl, drawing protests from the network’s southern affiliates. It kept him on at WABC radio in the New York market.

On May 5, 1958, when police refused to lower the lights, potentially allowing teenagers to “neck” in the dark at a Boston event, Freed told the crowd, “It looks like the Boston police don’t want you to have a good time.” As a result, Freed was arrested and charged with attempting to incite a riot, One local paper printed the opinion that Freed’s “jam sessions…tend to become the magnet for hoodlums whose jungle instincts are aroused by the caterwauling and mass hypnotism, particularly if enough police are not alerted.”

He was subsequently fired by WINS but continued to spin records for WABC and host a local version of Big Beat on WNEW-TV New York until November 1959 when he was fired from the network after “payola” accusations surfaced and he refused to sign a statement denying involvement. Freed said he had accepted gifts that didn’t influence airplay.

“Payola,” a contraction of the words “pay” and “Victrola” (an LP record player), refers to payments from record companies to play specific records, a practice that was controversial but not illegal at the time. Alan Freed and Dick Clark were the top DJs in the country and the focus of the investigation.

Dick Clark gave up all his musical interests when ordered to do so by ABC-TV. He admitted a $125 investment in Jamie Records had returned a profit of $11,900 and that, of the 163 songs he had rights to, 143 were given to him, but denied accepting payola. As Clark told Rolling Stone in 1989, the lesson he learned from the payola trial was: “Protect your ass at all times.”

Freed didn’t fare so well. He was convicted on two counts of commercial bribery—which was a crime—for accepting $2,700, which he claimed was only a token of gratitude. He paid a $300 fine and received a six-month suspended sentence. Accepting “payola” was put on the books as a misdemeanor offense later.

Blackballed by the industry, he never worked for a prestigious station again and drifted between small stations in California and Florida before dying a poor and bitter man on January 20, 1965, due to cirrhosis of the liver brought on by alcohol abuse. He was 43 years old.

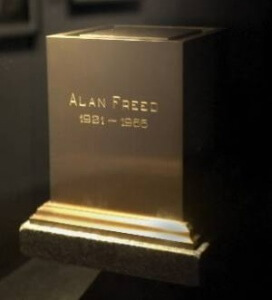

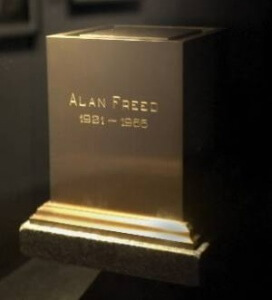

Freed was cremated and interred in Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, NY. In March 2002, his ashes were moved to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. Freed’s association with Cleveland was a large part of the decision to locate the museum there.

Thirty years ago, on January 23, 1986, he was in the first group inducted into the Hall of Fame, with Elvis Presley, James Brown, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ray Charles and others. The radio station that broadcasts from within the museum is named the Alan Freed Studio.

On August 1, 2014, the Hall of Fame removed his ashes from view and asked his family to come get them. Executive Director Greg Harris said that the original request to put the urn on view at the museum came from the Freed family. “We planned on returning them all along,” he said.

In 2002, then Rock Hall CEO Terry Stewart said, “I’m sure some people will find it unusual and others might find it morbid. It’s certainly appropriate in a rock ‘n’ roll sense to have his final resting place here.” The key word is final. There is no indication that Freed’s family intended to loan out his ashes.

The removal came just days after the museum opened an exhibit featuring Beyoncé’s costumes, including the black leotards she wore in her 2008 “Single Ladies” video. Harris defended the timing, saying, “Rock and roll isn’t just about yesterday. It continues to evolve, and we continue to embrace it and refine our operations.”

Perhaps it’s a fitting end for Freed’s ashes, considering that the man was rejected by the industry he helped to create. His family decided to keep his ashes in Cleveland at Lake View Cemetery. The Hall of Fame continues to pay tribute to Freed with other artifacts and sells a bronze-plated coin celebrating the inductees of 1986 for $32.39 at its gift shop. Rock on.

![]()